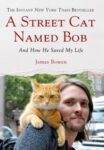

And How He Saved My Life, by James Bowen and Garry Jenkins, 2012

True story about a heroin addict in London, James Bowen, adopting this street cat (a “Ginger Tom”) in 2007, who ends up saving his life. What a wonderful gift this cat is from God to him. Because he had to care for this cat, it kept him from going back on heroin and gave his life meaning and richness. This cat, who refused to leave him, provided him the motivation to better his life, get completely off heroin, and provided the love and companionship and purpose he needed to stay off drugs. He healed rifts with his family. He could see beauty in the world again. What a wonderful tale, a true story. I learned about this book from the Poudre River Library’s monthly email on biographies. There are two more books in the series, and he has a website: www.hodder.co.uk and Twitter site @streetcatbob.

It is very easy reading but very engaging. I loved this book. You learn a lot about the programs there are for homeless people and addicts in London. Here are some interesting parts:

“Busking at James Street was a bit of a gamble as well. Technically speaking, I wasn’t supposed to be there.

‘The Covent Garden area is divided up very specifically into areas when it comes to street people. It’s regulated by officials from the local council, an officious bunch that we refereed to as Covent Guardians.

‘My pitch should have been on the eastern side of Covent Garden, near the Royal Opera House and Bow Street. That’s where the musicians were supposed to operate, according to the Covent Guardians. The other side of the piazza, the western side, was where the street performers were supposed to ply their trade. The jugglers and entertainers generally pitched themselves under the balcony of the Punch and Judy pub where they usually found a rowdy audience willing to watch them.

‘James Street, where I had begun playing, was meant to be the domain of the human statues…”

After “busking” for a year or so and being very successful once he started bringing Bob (who made it clear he wanted to come along), he gets falsely accused of threatening people and when he is cleared by a DNA test, he decides to change his occupation to a Big Issue magazine-seller, another interesting program provided to the homeless in London. Here’s his interview on the street with the coordinator, Sam:

“‘Hello, you two not busking today?’ she said, recognising me and Bob and giving him a friendly pat.

‘No, I’m going to have to knock that on the head,’ I said. ‘Bit of trouble with the cops. If I get caught doing it illegally again, I’m going to be in big trouble. Can’t risk it now I’ve got Bob to look after. Can I, mate?’

‘OK,’ Sam said, her face immediately signalling that she could see what was coming next.

‘So,’ I said, rocking up and down on my heels. ‘I was wondering –‘

‘Sam smiled and cut me off. ‘Well, it all depends on whether you meet the criteria,’ she said.

‘Oh yeah, I do,’ I said, knowing that as a person in what was known as ‘vulnerable housing’ I was eligible to sell the magazine.”

Here’s how he describes getting hooked on heroin:

“The next phase of my life was a fog of drugs, drink, petty crime — and, well, hopelessness. It wasn’t helped by the fact that I developed a heroin habit.

‘I took it at first simply to help me get to sleep at night on the streets. It anaesthetised me from the cold and the loneliness. It took me to another place. Unfortunately, it had also taken a hold of my soul as well. By 1998 I was totally dependent on it. I probably came close to death a few times, although, to be honest, I was so out of it at times that I had no idea.”

Here’s how selling the magazine helps homeless people in London:

“‘The Big Issue exists to offer homeless and vulnerably housed people the opportunity to earn a legitimate income by selling a magazine to the general public. We believe in offering “a hand up, not a hand out” and in enabling individuals to take control of their lives.'”

In London, there are Drug Dependency Units that help addicts kick the habit. Here he describes the end of a very long process:

“The prescription the counsellor had just given me was for my last dose of methadone. Methadone had helped me kick my dependence on heroin. But I’d now tapered down my usage to such an extent that it was time to stop taking it for good.

‘When I next came to the DDU in a couple of days’ time I would be given my first dose of a much milder medication, Subutex, which would ease me out of drug dependency completely. The counsellor described the process as like landing an aeroplane, which I thought was a good analogy. In the following months he would slowly cut back my dosage until it was almost nonexistent. As he did so, he said I would slowly drop back down to earth, landing — hopefully — with a very gentle bump.”…

“Coming off methadone wasn’t easy. In fact, it was really hard. I’d experience ‘clucking’ or ‘cold turkey’, a series of unpleasant physical and mental withdrawal symptoms…”

“I was confident at this point that I could do it. But at the same time I had an awful niggling feeling that I could fail and find myself wanting to score something that would make me feel better. But I just kept telling myself that I had to do this, I had to get over this last hurdle. Otherwise it was going to be the same the next day and the next day and the day after that. Nothing was going to change.

‘This was the reality that had finally dawned on me. I’d been living this way for ten years. A lot of my life had just slipped away. I’d wasted so much time, sitting around watching the days vanish. When you are dependent on drugs, minutes become hours, hours become days. It all just slips by; time becomes inconsequential, you only start worrying about it when you need your next fix. You don’t even care until then.”

He experiences a horrible 48 hours but he makes it through it because he had Bob right there with him, beside him, purring, or needing him to feed him, etc. Through it all, migraine headaches, hallucinations, restless leg syndrome, hot and cold. Here he describes it:

“That battle of wills that’s going on in your brain is very one-sided. The addictive forces are definitely stronger than those that are trying to wean you off the drugs.

‘At another point, I was able to see the last decade and what my addiction had done to me. I saw — and sometimes smelled — the alleys and underpasses where I’d slept rough, the hostels where I’d feared for my life, the terrible things I’d done and considered doing just to score enough to get me through the next twelve hours. I saw with unbelievable clarity just how seriously addiction screws up your life.”