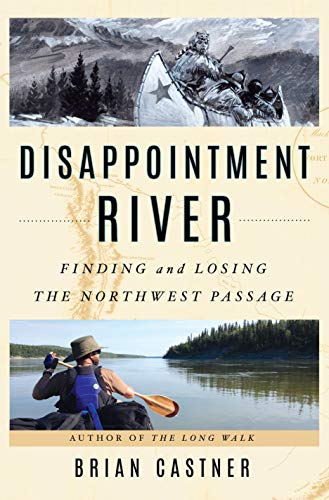

Finding and losing the Northwest Passage

by Brian Castner, 2018

Well-written book. I almost gave up on it because of the many French and Indian words and names I couldn’t pronounce, but I’m glad I stuck with it. He takes you on the Mackenzie River (the Deh Cho River) through Canada to the Arctic Ocean; first with Alexander Mackenzie and his crew in the 1780’s, and then with himself and 4 different guys. What a hard journey, then and now. It’s a miracle Alexander Mackenzie didn’t lose a single person, just a canoe and some supplies on one of the many portages they had to take to avoid rapids. And Brian and his fellows experienced the same “plagues of the Deh Cho:” terrible lightning, rain storms, wind, icy cold, unbearable heat and bugs, especially mosquitoes and bulldogs. In Fort Providence, the first town Brian and his first partner, David, reached, they didn’t secure their canoe and supplies. During the night, drunk Indians vandalized and stole or ruined most of their supplies. Brian contacted the outfitter (the one in Fort Smith who had told him not to worry), and that outfitter drove a new stove up to Brian to replace the one stolen.

What an adventure it was traveling with Brian and each of his buddies in turn. I feel like I was there, he is so good at description and conversation. Each person was unique but a blessing. David was strong and an uncomplaining workhorse. Brian got spoiled with him. When the canoe was ransacked, David just started cleaning up the mess. Then, on a particularly bad weather day or facing some major disappointment, he said to brush their teeth and sure enough, that helped. From then on, Brian remembered that, and it always made him feel better once he’d brushed his teeth.

Jeremy was a gay Jewish opera writer and he really wasn’t a help to Brian, except as company. He was fearful, weak, and inexperienced. Brian had to work doubly hard with Jeremy in the canoe.

Landon was next and he was an experienced sailor and military man, like Brian. He was a lucky charm; they found good camping spots and made good time.

Last was Senny, and he was a trooper – went with Brian to the far north – the Arctic Circle.

It was amazing that in the 1780’s, Alexander Mackenzie and his crew made it that far but it was all ice, even in July, so it couldn’t have been the northwest passage. Mackenzie was 200 years too early. Brian and Senny got there in 2016 and it was no longer ice at all. A charter boat came and picked them up on Garry Island.

Good book! I’ve been where I never want to go, and experienced something vicariously, thank goodness, because it wasn’t fun nor easy. Mackenzie’s crew in the 1780’s included 4 Indian wives; they were integral to the success of expeditions, proven beforehand. My respect for adventurers and explorers is great. They are brave and strong.

Here are some quotes from the book:

Europe was crazed by beaver fur, an epidemic on the order of the Dutch obsession with tulips, though far more practical and useful. Fibrous beaver hair was scraped from pelts and, after a soak in mercury, molded into felt hats. All manner of hats, women’s and men’s, top hats and military caps, fashionable stovepipes and the tricornered “continental” made famous by American revolutionaries. Once European and Russian stocks were all but exterminated, beaver furs became the most sought-after commodity extracted from North America.

from page 34, “Montreal, 1778”

It was nearly midnight when they stopped at the first small island to make camp; in the twilight, Mackenzie was amazed the horizon glowed “as clear as to see to write this.” Mackenzie was used to long summer days–Fort Chipewyan [chip-you-on] was the same rough latitude as his birthplace of Stornoway–but the phenomenon was increasing rapidly, as the voyageurs regummed the canoes after the long crossing.

In the rest of the pays d’en haut, the trees required to make and fix the birch-bark canoes were found all along the rivers. If one wished to invent ideal natural materials for boat construction–light and strong framing, water-resistance and pliable fastening binders, flexible sheeting–it would be hard to best cedar planks, watape spruce root, and birch bark. And unique in North America, they all grow, together, in the one place they are needed most, as if nature first carved the system of rivers and streams to breach the continent and then grew the perfect boats to traverse it. This was true to the south, but now, for the first time, as they hopped from gravel speck to gravel speck, if they broke a canoe hard, they would have to repair it with the supplies they carried or make do without. And they were already short one canoe, lost in the rapids of the Slave.

from pages 130 and 131, “Shoot the Messenger, June 1789”

I wanted to talk to Mark and Gilly more, but my stomach was rumbling. Our guidebook said you could get a hot meal at the Snowshoe Inn.

“David and I are going into town to get dinner. Are you going to the bar later?” I asked, but Mark laughed.

“Only white people go to the bar. It’s too expensive,” he said. “Indians buy a case a day and go home.”

“But you guys gotta be careful,” Gilly said. “Here, you’re okay, because we’re watching your canoe. We’ll keep an eye on it for you but downriver they’ll steal your stuff.”

“Especially in Wrigley,” Mark said. “They’re terrible in Wrigley. Thieves. But here in Fort Prov, you’re fine.”

Our walk into town was very short. Ravens had taken over the belfry of the church, and the scattered homes consisted of single- and double-wide trailers, some well maintained, some not. A few had teepees, for drying fish, skinned with plastic tarps to keep the smoke in. For curiosity’s sake, I tried to spot the house of the richest man in town, a habit I continued the rest of the trip, but didn’t spot an obvious Old Man Potter in Bedford Falls.

A few indigenous locals stood in a group outside the Snowshoe Inn, and when we passed, they asked us to buy them beer inside. One woman, Edna, had the small wide-spaced eyes indicative of fetal alcohol syndrome. She was already intoxicated and asked what the two new white guys in town were doing.

“We’re paddling the whole Mackenzie River,” I said.

An old man in a plaid shirt shook his head. “You’re crazy,” he said.

from page 148, “Thunderstorms and Raids, June 2016”

The magnetic north pole moves, and when Mackenzie made his journey, it was located at modern-day Victoria Island, just above the Canadian mainland. Mackenzie knew about the magnetic variation from true north, correctly noted in his journal that on Lake Superior the two roughly aligned, and calibrated his compass when he could. But as he moved farther north, the error increased quickly; the magnetic north pole actually lay more to his east than north. This positive declination skewed every measurement he made. When he stood on the riverbank and looked in the direction that his compass claimed was north, in reality he was looking northeast. When he thought he was paddling northwest, he was really paddling due north. And the farther north he went, the more incorrect every measurement proved.

From the moment he made the turn at the Camsell Bend, Mackenzie was headed in the wrong direction, and staring at his bewitched compass, he had no idea.

from page 176, “The Plagues of the Deh Cho, July 2016”

And yet, as our tiny canoe floated to the base of those bulwarks, the Ramparts seemed to diminish in strength, overwhelmed by the width and depth of the Deh Cho. Nothing compared with the scale of the river or withstood its scrutiny. Every mountain bowed to foothills, adjoining streams but trickles, and at times even the sky seemed to shrink. Each lost its sublimity, cowed to submission. And us, just bits of yeast, alone, insignificant motes upon the water, subservient in all ways to the current. If even the Ramparts were so reduced, then what were we? The vast river swallowed all.

Of all the plagues of the Deh Cho, the worst is emptiness.

from page 214, “Rapids without Rapids, July 2016”

Landon and I arrived in Fort Good Hope two days early, and we spent those days with Wilfred Jackson and his family, in their modest clapboard heap heaving in the permafrost. Wilfred calls it a Bed & Breakfast, but it’s more like a Mattress & Help Yourself The Kitchen Is Over there.

from page 221, “Fort Good Hope to Tsiigehtchic, July 2016”

Almost all the old-timers are dead,” Wilfred says, and worse, few young people are learning to live on the land. Wilfred said that in Tsiigehtchic–a place he pronounced “SIG-a-check”–they still make dry fish, the traditional smoked trout, pickerel, char, grayling. A woman comes to Fort Good Hope to sell it, for as much as a hundred dollars a fish. “People go crazy for it,” Rayuka said in amazement. I could tell this bothered Wilfred, not only that the young people of his town won’t take up this lucrative business, but that they would rather buy dry fish than smoke it themselves.

from page 226, “Fort Good Hope to Tsiigehtchic, July 2016”

This is near the end of the trip and is a description of Richard’s Island, which seems to be the ONLY pretty part of the entire trip:

Richards Island’s hills look like an Irish postcard. The Yaya River itself was green, made not of Deh Cho water but of rain and snow filtered through that gentle island. We stopped at a rocky beach and drank freshwater and made dinner, Vegetarian Chili–with only a few days left we were eating all our favorites–and I stretched my legs by walking up a slope of twisted brush.

It had been sunny for two days. I turned my face to the sky to feel the warmth, but when I did, I saw the return of the mare’s tails and mackerel scales [clouds that portent a bad storm coming]. I didn’t tell Senny.

We paddled a little father and found a narrow sandy shelf tucked into a cove, barely big enough for the tent. While I set up camp, Senny scrambled up the slope and then called to me, excited. He had discovered tundra.

Rolling mounds stretched to the horizon. Beauty in miniature, as giant honeybees buzzed like zeppelins over blueberry bushes and soft beds of moss and lupine. Senny found a king-sized section that sank like marshmallow under his feet, and he stretched out, spread eagle. I rested my aching back and stared at the sky. Senny fell sleep [sic] in the lichen. I picked at club moss that looked like tiny pine trees laden with black berries, ate one, and then thought better of experimenting with unknown foraging and stopped.

I lay down and considered the perfect blue. Clouds rolled past. The smell was intoxicating, mulched soil and pollen and cracked mint. Warm sun on one side of my face, cool breeze on the other. My head net kept the mosquitoes off, and my brimmed hat shaded the sun from my eyes, and my back, spasmed from a thousand miles of paddling, eased into the moss.

It was a place of peace, the likes of which I had not yet experienced on the river. A moment of pure solemnity.

“This might be worth the whole trip,” I said.

“Pretty close,” Senny said, groggy. “I feel like I lay down in the soap aisle. With mattresses.

from page 257 and 258, “Into the Earth Sponge, July 2016”

Awgeenah [the English Chief, a Chipewyan Indian chief accompanying Mackenzie] once told Mackenzie the story of his people. This is what he said:

‘At the first, the globe was one vast and entire ocean, inhabited by no living creature, except a mighty bird, whose eyes were fire, whose glances were lightning, and the clapping of whose wings were thunder. On his descent to the ocean, and touching it, the earth instantly arose, and remained on the surface of the waters.

‘The great bird, having finished his world, made an arrow, which was to be preserved with great care, and to remain untouched; but that [we] were so devoid of understanding, as to carry it away; and the sacrilege so enraged the great bird, that he has never since appeared.

‘Immediately after [our] death, [we] pass into another world, where [we] arrive at a large river, on which [we] embark in a stone canoe, and that a gentle current bears [us] on to an extensive lake, in the centre of which is a most beautiful island.

‘In the view of this delightful abode, [we] receive that judgement for [our] conduct during life, which terminates [our] final state and unalterable allotment. If [our] good actions are declared to predominate, [we] are landed upon the island, where there is to be no end to [our] happiness.

‘But if [our] bad actions weigh down the balance, the stone canoe sinks at once, and leaves [us] up to our chins in the water, to behold and regret the rewards enjoyed by the good, and eternally struggling, but with unavailing endeavors, to reach the blissful island from which [we] are excluded for ever.

from pages 264 and 265, “The Highest Part of the Island, July 1789”

But where was that? Where had they ended up? Mackenzie called Awgeenah, and the men began to hike.

“I went with the English Chief to the highest part of the Island from which we could see the Ice in a whole Body extending from S.W. by Compass to the Eastward as far as we could see.”

This was surely the girdle of impenetrable ice that encircled the North Pole. All learned geographers agreed that the warm and open Hyperborean Sea was guarded by this pack of floes. If that ice extended even to the mouth of this river in the warmth of July, then the way was perpetually blocked. This was no highway to Russia and China, It was a taunting dead-end road, a cruel plug in the mouth of all of his commercial aspirations.

Mackenzie had failed. This northwest passage would be forever encased in ice.

“We were stopped by the Ice ahead,” he concluded, “and we landed at the limit of our Travels.”

And that is the story of how Alexander Mackenzie traveled the river that would bear his name, and how Awgeenah, the English Chief, his Chipewyan partner in all things, the heir to Matonabbee who became the greatest of “the great travelers of the known world,” stood on the shore of the Arctic Ocean for a second time.

from page 266, “The Highest Part of the Island, July 1789”

I needed to walk, so Senny and I hiked up Mackenzie and Awgeenah’s hill to get a better view of the ocean. To the west, the island stretched on and on in a wedge, a carpet of orange moss and pale green lichen, small bushes that dug themselves holes to escape the wind. We tromped the incline, and the land fell away as cliffs to our south, a wide bay to the north. The whole thing smelled unexpectedly rich and earthy as we balanced on unsure footing, tussock to tussock, like soft sand. Up the slope, we gained a ridge and looked out, our faces to the north wind.

We saw open water. Not a sliver of ice anywhere. The ocean was not a shocking polar blue, as you imagine from the movies. It was dull, the color of a worn-out coffee mug, all the way to the northern horizon.

Senny didn’t bother to pull out his camera. “Photos never look like eyeballs, which drives me nuts,” he said. So I put my camera away too, and we just took in the view together.

I knew it was likely I would see open water–since 1980, summer pack ice in the Arctic is down 80 percent, as the whole region warms twice as fast as the rest of the planet–but it was still unsettling, knowing how the ice completely shaped Mackenzie’s experience. I had only seen that single dirty lump just south of Tsiigehtchic, but for Mackenzie the ice was definitive. And permanent, because the climate was fixed; the concept that it could change was more fantastical than his giant sea horse.

I checked my GPS and took a photograph of the screen. It read 69 degrees 26.5 minutes north, “the extent of our travels,” as Mackenzie said. In 1915, Ernest Shackleton’s famous ship, the Endurance, was crushed in the ice, near Antarctica, at 69 degrees 5 minutes south. In that context, it really felt like we had accomplished something.

All I had done, though, after 1,125 miles of paddling, was make it to a place that Mackenzie did not want to be. My success was his failure. There was no pot of Chinese gold waiting for him at the end of this journey. He would return empty-handed.

And yet, I had just canoed his Northwest Passage. The way is open. Mackenzie was simply two hundred years too early.

from page 272, “A Sea of Ice, Frozen No More, July 2016”