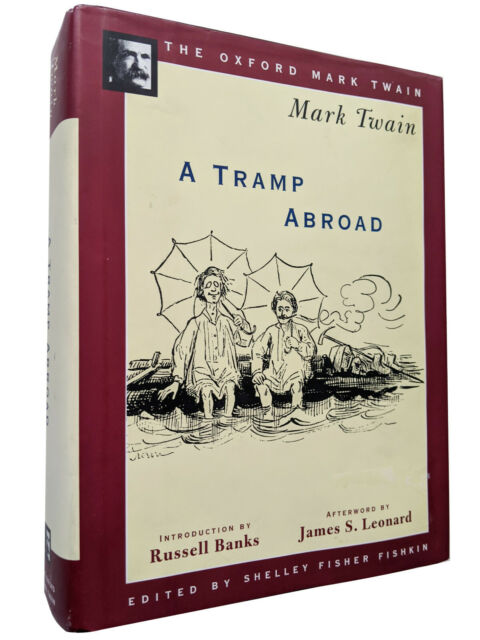

by Mark Twain, 1880

Delightful tramp through Germany, Switzerland, and Italy with Mark Twain and his mysterious agent, Mr. Harris, in the late 1800’s; funny, beautiful, and educational. The landscapes in Germany and Switzerland are beautiful, except there seem to be some villages in Switzerland that are full of manure (walking through “fertilizer juice.” His descriptions of the countryside make me long to see Europe, but before cars, planes, industrialism, and terrible wars. He is hilarious! He comes up with preposterous scientific theories that he tries to get real scientists to publish. He boils a thermometer and comes up with elevations of 200,000 feet. He sees that the moon never rises above a certain mountain so proposes the moon never goes higher than 12,000 feet. He describes mountain climbing attempts; one by telescope and another, which I think is a simple walk of less than a day, but with him it’s a huge undertaking involving about 17 guides, 22 bartenders, 18 chaplains, miles of rope, ladders, umbrellas, mules, and on and on. They get lost almost immediately and it takes them 7 days to get to the hotel, with many a mishap/disaster along the way. He learns that glaciers move so decides to go back down a mountain on a glacier, and waits, and waits, and waits, checking the time-tables, etc.

Throughout the book, he retells legends and stories from old and he includes illustrations on almost every page. A few of the drawings are his and they are hilarious. At the end, he talks about wanting to eat American food again and drink American coffee. Sounds like European food and coffee were awful back in the 1800’s. He makes a list of the meal he has requested once he arrives in New York City and it includes EVERY food and drink he’s missed. I LOVED this book, and I LOVE Mark Twain.

Here are some of my favorite lines:

I got up and went into the west balcony and saw a wonderful sight. Away down on the level, under the black mass of the Castle, the town lay, stretched along the river, its intricate cobweb of streets jeweled with twinkling lights; there were rows of lights on the bridges; these flung lances of light upon the water, in the black shadows of the arches; and away at the extremity of all this fairy spectacle blinked and glowed a masses multitude of gas jets which seemed to cover acres of ground; it was as if all this fairy spectacle blinked and glowed a massed multitude of gas jets which seemed to cover acres of ground; it was as if all the diamonds in the world has been spread out there.

from page 31 describing Heidelberg by night

You think a cat can swear. Well, a cat can; but you give a blue-jay a subject that calls for his reserve-powers, and where is your cat? Don’t talk to me–I know too much about this thing. And there’s yet another thing: in the one little particular of scolding–just good, clean, out-and-out scolding–a blue-jay can lay over anything, human or divine. Yes, sir, a jay is everything that a man is. A jay can cry, a jay can laugh, a jay can fee shame, a jay can reason and plan and discuss, a jay likes gossip and scandal, a jay has got a sense of humor, a jay knows when he is an ass just as well as you do–maybe better. If a jay ain’t human, he better take in his sign, that’s all. Now I’m going to tell you a perfectly true fact about some blue-jays.

from page 37 in Blue-jays as Talkers

Germany, in the summer, is the perfection of the beautiful, but nobody has understood, and realized, and enjoyed the utmost possibilities of this soft and peaceful beauty unless he has voyaged down the Neckar on a raft. …

We went slipping silently along, between the green and fragrant banks, with a sense of pleasure and contentment that grew, and grew, all the time. Sometimes the banks were over-hung with thick masses of willows that wholly hid the ground behind; sometimes we had noble hills on one hand, clothed densely with foliage to their tops, and on the other hand open levels blazing with poppies, or clothed in the rich blue of the corn-flower; sometimes we drifted in the shadow of forests, and sometimes along the margin of long stretches of velvety grass, fresh and green and bright, a tireless charm to the eye. And the birds!–they were everywhere; they swept back and forth across the river constantly, and their jubilant music was never stilled.

It was a deep and satisfying pleasure to see the sun create the new morning, and gradually, patiently, lovingly clothe it on with splendor after splendor, and glory after glory, till the miracle was complete. How different is this marvel observed from a raft, from what it is when one observes it through the dingy windows of a railway station in some wretched village while he munches a petrified sandwich and waits for the train.

from pages 126 and 127, Voyaging on a Raft

Men and women and cattle were at work in the dewy fields by this time. The people often stepped aboard the raft, as we glided along the grassy shores, and gossiped with us and with the crew for a hundred yards or so, then stepped ashore again, refreshed by the ride.

Only the men did this; the women were too busy. The women do all kinds of work on the continent. They dig, they hoe, they reap, they sow, they bear monstrous burdens on their backs, they shove similar ones long distance on wheelbarrows, they drag the cart when there is no dog or lean cow to drag it,–and when there is, they assist the dog or cow. Age is no matter,–the older the woman, the stronger she is, apparently. On the farm a woman’s duties are not defined,–she does a little of everything; but in the towns it is different, there she only does certain things, the men do the rest. For instance, a hotel chambermaid has nothing to do but make beds and fires in fifty or sixty rooms, bring towels and candles, and fetch several tons of water up several flights of stairs, a hundred pounds at a time, in prodigious metal pitchers. She does not have to work more than eighteen or twenty hours a day, and she can always get down on her knees and scrub the floors of halls and closets when she is tired and needs a rest.

from page 123 in “Down the River”

He recounts the German legend of Lorelei and even includes the music for it.

From Baden-Baden we made the customary trip into the Black Forest. We were on foot most of the time. One cannot describe those noble woods, nor the feeling with which they inspire him. A feature of the feeling, however, is a deep sense of contentment; another feature of it is a buoyant, boyish gladness; and a third and very conspicuous feature of it is one’s sense of the remoteness of the work-day world and his entire emancipation from it and its affairs.

Those woods stretch unbroken over a vast region; and everywhere they are such dense woods, and so still, and so piney and fragrant. The stems of he trees are trim and straight, and in many places all the ground is hidden for miles under a thick cushion of moss of a vivid green color, with not a decayed or ragged spot in its surface, and not a fallen leaf or twig to mar its immaculate tidiness. A rich cathedral gloom pervades the pillared aisles; so the stray flecks of sunlight that strike a trunk here and a bough yonder are strongly accented, and when they strike the moss they fairly seem to burn. But the weirdest effect, and the most enchanting, is that produced by the diffused light of the low afternoon sun; no single ray is able to pierce its way in, then, but the diffused light takes color from moss and foliage, and pervades the place like a faint, green-tinted mist, the theatrical fire of fairyland. The suggestion of mystery and the supernatural which haunts the forest at all times, is intensified by this unearthly glow

From pages 13 and 14 describing the Black Forest. He used “wierdest” in the above sentence.

Now and then, while we rested, we watched the laborious ant at his work. I found nothing new in him,–certainly nothing to change my opinion of him. It seems to me that in the matter of intellect the ant must be a strangely overrated bird. During many summers, now, I have watched him, when I ought to have been in better business, and I have not yet come across a living ant that seemed to have any more sense than a dead one. I refer to the ordinary ant, of course; I have had no experience of those wonderful Swiss and African ones which vote, keep drilled armies, hold slaves, and dispute about religion. Those particular ants may be all that the naturalist paints them, but I am persuaded that the average ant is a sham. I admit his industry, of course; he is the hardest working creature in the world,–when anybody is looking,–but his leather-headedness is the point I make against him. He goes out foraging, he makes a capture, and then what does he do? Go home? No,–he goes anywhere but home. He doesn’t know where home is. His home may be only three feet away, –no matter, he can’t find it. He makes his capture, as I have said; it is generally something which can be of no sort of use to himself or anybody else; it is usually seven times bigger than it ought to be; he hunts out the awkwardest pace to take hold of it; he lifts it bodily up in the air by main force, and starts: not toward home, but in the opposite direction; not calmly and wisely, but with a frantic haste which is wasteful of his strength; he fetches up against a pebble, and instead of going around it, he climbs over it backwards dragging his booty after him, tumbles down on the other side, jumps up in a passion, kicks the dust off his clothes, moistens his hands, grabs his property viciously, yanks it this way then that, shoves it ahead of him a moment, turns tail and lugs it after him another moment, gets madder and madder, then presently hoists it into the air and goes tearing away in an entirely new direction; comes to a weed; it never occurs to him to go around it; no, he must climb it; and he does climb it, dragging his worthless property to the top–which is as bright a thing to do as it would be for me to carry a sack of flour from Heidelberg to Paris by way of Strasburg steeple; when he gets up there he finds that that is not the place; takes a cursory glance at the scenery and either climbs down again or tumbles down, and starts off once more–as usual, in a new direction….

from pages 215 and 216, ‘The Ant a Fraud’

We were satisfied that we could walk to Oppenau in one day, now that we were in practice; so we set out next morning after breakfast determined to do it. It was all the way down hill, and we had the loveliest summer weather for it. So we set the pedometer and then stretched away on an easy, regular stride, down through the cloven forest, drawing in the fragrant breath of the morning in deep refreshing draughts, and wishing we might never have anything to do forever but walk to Oppenau and keep on doing it and then doing it over again.

Now the true charm of pedestrianism does not lie in the walking, or in the scenery, but in the talking. The walking is good to time the movement of the tongue by, and to keep the blood and the brain stirred up and active; the scenery and the woodsy smells are good to bear in upon a man an unconscious and unobtrusive charm and solace to eye and soul and sense; but the supreme pleasure comes from the talk. It is no matter whether one talks wisdom or nonsense, the case is the same, the bulk of the enjoyment lies in the wagging of the gladsome jaw and the flapping of the sympathetic ear.

And what a motley variety of subjects a couple of people will casually rake over in the course of a day’s tramp! There being no constraint, a change of subject is always in order, and so a body is not likely to keep pegging at a single topic until it grows tiresome. We discussed everything we knew during the first fifteen or twenty minutes, that morning, and then branched out into the glad, free boundless realm of the things we were not certain about.

from pages 221 and 222, ‘Tramping and Talking’

We do not work on Sunday, because the commandment forbids it; the Germans do not work on Sunday, because the commandment forbids it. We rest on Sunday, because the commandment requires it; the Germans rest on Sunday, because the commandment requires it. But in the definition of the word “rest” lies all the difference. With us, its Sunday meaning is, stay in the house and keep still; with the Germans its Sunday and week-day meanings seems to be the same,–rest the tired part, and never mind the other parts of the frame; rest the tired part, and use the means best calculated to rest that particular part. Thus: If one’s duties have kept him in the house all the week, it will rest him to be out on Sunday; if his duties have required him to read weighty and serious matter all the week, it will rest him to read light matter on Sunday; if his occupation has busied him with death and funerals all the week, it will rest him to go to the theatre Sunday night and put in two or three hours laughing at a comedy; if he is tired with digging ditches or felling trees all the week, it will rest him to lie quiet in the house on Sunday…

The Germans remember the Sabbath day to keep it holy, by abstaining from work, as commanded; we keep it holy by abstaining from work, as commanded, and by also abstaining from play, which is not commanded.

from pages 231 and 232 on ‘A German Sabbath’

I suppose the Fremersberg is very low-grade music; I know, indeed, that it must be low-grade music, because it so delighted me, warmed me, moved me, stirred me, uplifted me, enraptured me, that I was full of cry all the time, and mad with enthusiasm. My soul had never had such a scouring out since I was born.

from pages 236 and 237, ‘Grades of Music’

While I was feeling these things, I was groping, without knowing it, toward an understanding of what the spell is which people find in the Alps, and in no other mountains,–that strange, deep, nameless influence, which, once felt, cannot be forgotten,–once felt, leaves always behind it a restless longing to feel it again,–a longing which is like homesickness; a grieving, haunting yearning, which will plead, implore, and persecute till it has its will.

from page 356, ‘The Spirit of the Alps’

…But I doubted if they ever had much real fun, outside of the mere magnificent exhilaration of the tramp through the green valleys and the breezy heights; for they were almost always alone, and even the finest scenery loses incalculably when there is no one to enjoy it with.

from page 368, ‘Embryo Lions’

A walk from St. Nicholas to Zermatt is a wonderful experience…There is nothing tame, or cheap, or trivial,–it is all magnificent. That short valley is a picture gallery of a notable kind, for it contains no mediocrities; from end to end the Creator has hung it with His masterpieces.

from page 408, ‘The Matterhorn’

The Alps and the glaciers together are able to take every bit of conceit out of a man and reduce his self-importance to zero if he will only remain within the influence of their sublime presence long enough to give it a fair and reasonable chance to do its work.

from page 466, ‘The Movements of Glaciers’

That was a blazing hot day, and it brought a persistent and persecuting thirst with it. What an unspeakable luxury it was to slake that thirst with the pure and limpid ice-water of the glacier!…Everywhere among the Swiss mountains we had at hand the blessing–not to be found in Europe except in the mountains–of water capable of quenching thirst. Everywhere in the Swiss highlands brilliant little rills of exquisitely cold water went dancing along by the roadside, and my comrade and I were always drinking and always delivering our deep gratitude.

But in Europe everywhere except in the mountains, the water is flat and insipid beyond the power of words to describe. It is served lukewarm; but no matter, ice could not help it; it is incurable flat, incurably insipid. It is only good to wash with; I wonder it doesn’t occur to the average inhabitant to try it for that.

from page 536, ‘Water as Drink’