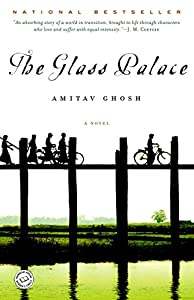

by Amitav Ghosh, 2000

Historical fiction about Burma and India in the late 1800s through mid-1900s. Learn about the royal family of Burma and their ousting by the British, learn about teak harvesting in Burma and rubber plantations in Malaysia. Learn about colonialism through the eyes of those colonized (Indians). Also learn that many Indians left India and its caste system and found much wealth and success in other countries such as Burma where they were free to be whatever their talent, ambition and hard work allowed. I liked this book. I liked how he described Burma pre-British. It sounded so beautiful. The Burmese royal family was sent into exile to Ratnagiri, India, and I like how he described that, too. I guess it has changed, though, because one of the characters in the book travels there later in the 1900s and it is no longer quite so beautiful.

Here are some quotes from the book:

In the dry season, when the earth cracked and the forests wilted, the streams would dwindle into dribbles upon the slope, barely able to shoulder the weight of a handful of leaves, mere trickles of mud between strings of cloudy riverbed pools. This was the season for the timbermen to comb the forest for teak. The trees, once picked, had to be killed and left to dry, for the density of teak is such that it will not remain afloat while its heartwood is moist. The killing was achieved with a girdle of incisions, thin slits carved deep into the wood at a height of four feet and six inches off the ground (teak being ruled, despite the wildness of its terrain, by imperial stricture in every tiny detail.)

The assassinated trees were left to die where they stood, sometimes for three years or even more. It was only after they had been judged dry enough to float that they were marked for felling. That was when the axemen came, shouldering their weapons, squinting along the blades to judge their victims’ angles of descent.

It was from Doh Say that Rajkumar learnt of the many guises in which death stalked the lives of oo-sis: The Russell’s viper, the maverick log, the charge of the wild buffalo. Yet the worst of Doh Say’s fears had to do not with these recognizable incarnations of death, but rather with one peculiarly vengeful form of it. This was anthrax, the most deadly of elephant diseases.

Anthrax was common in the forests of central Burma and epidemics were hard to prevent. The disease could lie dormant in grasslands for as long as thirty years. A trail or pathway, tranquil in appearance and judged to be safe after lying many years unused, could reveal itself suddenly to be a causeway to death. In its most virulent forms anthrax could kill an elephant in a matter of hours. A gigantic tusker, a full fifteen arms’ length off the ground, could be feeding peacefully at dusk and yet be dead at dawn. An entire working herd of a hundred elephants could be lost within a few days…

…The workings of their digestive systems do not stop with the onset of the disease; their intestines continue to produce dung after the excretory passage has been sealed, the unexpurgated fecal matter pushing explosively against the obstructed anal passage.

“The pain is so great,” said Doh Say, “that a stricken elephant will attack anything in sight. It will uproot trees and batter down walls. The tamest cows will become maddened killers; the gentlest calves will turn upon their mothers.”

As a rule, Rajkumar never challenged Uma on political matters. But he was on edge too now, and something snapped. “You have so many opinions, Uma–about things of which you know nothing. For weeks now I’ve heard you criticizing everything you see: the state of Burma, the treatment of women, the condition of India, the atrocities of the Empire. But what have you yourself ever done that qualified you to hold these opinions? Have you ever built anything? Given a single person a job? Improved anyone’s life in any way? No. All you ever do is stand back, as though you were above all of us, and you criticize and criticize. Your husband was as fine a man as any I’ve ever met, and you hounded him to his death with your self-righteousness–“

…Yet by the end of Arjun’s description, Dinu felt that he could see the hill in his head. Of those who listened to Arjun’s account, he alone was perhaps fully aware of the extreme difficulty of achieving such minuteness of recall and such vividness of description: he was awed both by the precision of Arjun’s narrative and by the off-handed lack of self-consciousness with which it was presented.

“Arjun,” he said, fixing him with his dour, unblinking stare. “I’m amazed..you described that hill as though you’d remembered every little bit of it.”

“Of course,” said Arjun. “My CO says that, under fire, you pay with a life for every missed detail.”

This too made Dinu take notice. He’d imagined that he knew the worth of observation, yet he’d never conceived that its value might be weighed in lives. There was something humbling about the thought of this. He’d regarded a soldier’s training as being, in the first instance, physical, a matter of the body. It took just that one conversation to show him that he had been wrong…

“How did you acquire thee books?” she asked.

“It was hard . . .” He laughed. “I made friends with ragpickers and they saved them for me. The foreigners who live in Yangon–the diplomats and aid-workers and so on–they tend to read a lot . . . there’s not much else for them to do, you see . . . they’re watched all the time . . . They bring books and magazines with them and from time to time they throw them away . . . Fortunately the military does not have the imagination to control their trash . . . These things find their way to us. All these bookcases–their contents were gathered one at a time, by ragpickers…

…But she is the only leader I’ve ever been able to believe in.”

“Why?”

“Because she’s the only one who seems to understand what the place of politics is . . . what it ought to be . . . that while misrule and tyranny must be resisted, so too must politics itself . . . that it cannot be allowed to cannibalize all of life, all of existence. To me this is the most terrible indignity of our condition–not just in Burma but in many other places too . . . that politics has invaded everything, spared nothing . . . religion, art, family . . . it has taken over everything. . . there is no escape from it . . . and yet what could be more trivial in the end? She understands this . . . only she . . . and this is what makes her much greater than a politician . . .”

Very educational book with deep insights and a good heart. If I was a person that re-reads books, this would need to be one, read slowly and carefully, taking in the depth of knowledge this author so deftly imparts.