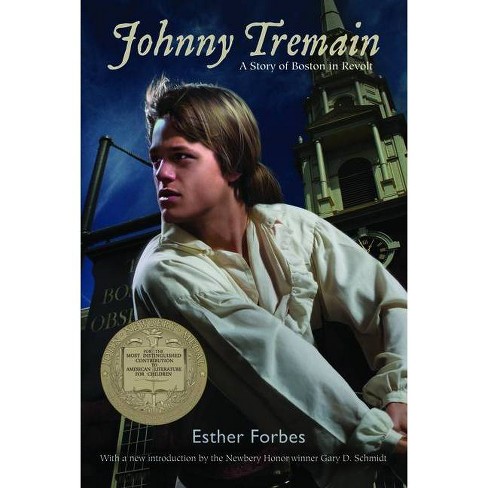

by Esther Forbes, 1943

What a wonderful book. I loved being with Johnny Tremain in Boston in the 1770s. It was on the Book-a-Day calendar from Christie: “For fans of The Simpsons: Can you recall what novel about the American Revolution captivated that not-so-eager reader Bart? ANSWER: Esther Forbes’s novel of revolutionary-era Boston, Johnny Tremain, which won the Newbery Medal in 1944.”

The main character, Johnny Tremain, is a 14-year-old boy orphaned in Boston, apprenticing as a silversmith. He burns his hand with molten silver, due to the deceit of a fellow apprentice, Dove. Johnny has to strike out on his own and we experience his loneliness and despair, but he rises above it and finds a hope and a future. He meets Rab, a kind and wise boy a couple of years older than Johnny. Rab befriends Johnny and hires him to deliver papers. Johnny learns to love and ride horses, in particular, Goblin, a horse nobody but he could ride. He delivers the Boston Observer to homes and businesses. He also delivers messages and news to the likes of Paul Revere, John Hancock, Samuel Adams, and others. The Revolution begins. Rab leaves Boston first in order to fight in the battle of Lexington, the very first battle of the war. Unfortunately, the British outmanned and outgunned them in the first battle and Rab is hit with many bullets before he could even shoot his gun. Johnny vows to join the fight as soon as Dr. Warren fixes his burnt and twisted hand so that he can hold a gun…Fantastic book. Takes you into the time of the Revolution. It is considered children’s literature, but it is 300 pages long and the language, characters, and plot seem like an adult book to me.

Here are some of my favorite parts of the book and also some that helped me understand the historical setting of Boston in the 1770s:

“Once, as they sat in the attic toasting cheese and muffins by their hearth, the older boy asked why he went about calling people ‘squeak-pigs’ and things like that. Johnny was always ready to do his share, or more than his share, in fanning up friendship–or enmity. Sometimes it seemed to Rab he did not much care which.

‘Why do you go out of your way to make bad feeling?’

Johnny hung his head. He could not think why.

‘And take Merchant Lyte. Everybody along Long Wharf knows you called him a gallows bird. He’s not used to it.’ Was it fun, he wondered–going about letting everybody who got in your way have it?

After that Johnny began to watch himself. For the first time he learned to think before he spoke. He counted ten that day he delivered a paper at Sam Adams’s big shabby house down on Purchase Street and the black girl flung dishwater out of the kitchen door without looking, and soaked him. If he had not counted ten, he would have told her what he thought of her, black folk in general, and thrown in a few cutting remarks about her master–the most powerful man in Boston. But counting ten had its rewards. Sukey apologized handsomely. In the past he had never given anyone time to apologize. Her ‘oh, little master, I’se so sorry!! Now you just step right into de kitchen and I’ll dry up dem close–and you can eat an apple pie as I dries,’ pleased him. And in the kitchen sat Sam Adams himself, inkhorn and papers before him. He had a kind face, furrowed, quizzical, crooked-browed. As Sukey dried and Johnny ate hie pie, Mr. Adams watched him, noted him, marked him, said little. But ever after when Johnny came to Sam Adams’s house, he was invited in and the great leader of the gathering rebellion would talk with him in that man-to-man fashion, which won so many hearts. He also began to employ him and Goblin to do express riding for the Boston Committee of Correspondence. All this because Johnny had counted ten. Rab was right. There was no point in going off ‘half-cocked.’ (from pages 116-117; Chapter V. The Boston Observer)

“England had, by the fall of 1773, gone far in adjusting the grievances of her American colonies. But she insisted upon a small tax on tea. Little money would be collected by this tax. It worked no hardship on the people’s pocketbooks: only threepence the pound. The stubborn colonists, who were insisting they would not be taxed unless they could vote for the men who taxed them, would hardly realize that the tax had been paid by the East India Company in London before the tea was shipped over here. After all, thought Parliament, the Americans were yokels and farmers–not political thinkers. And the East India tea, even after that tax was paid, would be better and cheaper than any the Americans ever had. Weren’t the Americans, after all, human beings? Wouldn’t they care more for their pocketbooks than their principles?” (from page 123, Chapter VI. Salt-Water Tea)

“Here was none of the usual hustle and bustle. Few of the crew were in sight, but hundreds of spectators gathered every day merely to stare at them. Johnny saw Rotch, the twenty-three-year-old Quaker who owned the Dartmouth, running about in despair. The Governor would not let him leave. The Town would not let him unload. Between them he was a ruined man. He feared a mob would burn his ship. There was no mob, and night and day armed citizens guarded the ships. They would see to it that no tea was smuggled ashore and that no harm was done to the ships. Back and forth paced the guard. Many of their faces were familiar to Johnny. One day even John Hancock took his turn with a musket on his shoulder, and the next night he saw Paul Revere.” (from page 142, Chapter VI. Salt-Water Tea)

“But when that bill came–the fiddler’s bill–that bill for the tea, it was so much heavier than anyone expected, Boston was thrown into a paroxysm of anger and despair. There had been many a moderate man who had thought the Tea Party a bit lawless and was now ready to vote payment for the tea. But when these men heard how cruelly the Town was to be punished, they swore it would never be paid for. And those other thirteen colonies. Up to this time many of them had had little interest in Boston’s struggles. Now they were united as never before. The punishment united the often jealous, often indifferent, separate colonies, as the Tea Party itself had not.

“Sam Adams was so happy his hands shook worse than ever.

“For it had been voted in far-off London that the port of Boston should be closed–not one ship might enter, not one ship might leave the port, except only His Majesty’s warships and transports, until the tea was paid for. Boston was to be starved into submission.

“On that day, that first of June, 1774, Johnny and Rab, like almost all the other citizens, did no work, but wandered from place to place over the town. People were standing in angry knots talking, gesticulating, swearing that yes, they would starve, they would go down to ruin rather than give in now. Even many of the Tories were talking like that, for the punishment fell equally heavily upon the King’s most loyal subjects in Boston and on the very ‘Indians’ who had tossed the tea overboard. This closing of the port of Boston was indeed tyranny; this was oppression; this was the last straw upon the back of many a moderate man.” (from pages 153-154; Chapter VII. The Fiddler’s Bill)

“As he came back from Milton, riding the long lonely stretch of the Neck, with the gallows and the town gates still before him, Johnny realized how long ago it was that he had burned his hand, and how he had hated Dove when he found out the part he had played in that accident. How he had sworn to get even with him (the lying hypocrite–telling old Mr. Lapham that all he had meant to do was to teach a pious lesson). Now, as he saw Dove daily about the Afric Queen, he could hardly remember this feeling of hatred, his oaths of vengeance. Seemingly hatred and desire for revenge do not last long. He had made new friends. The old world of the Lapham shop and house was gone. Yet he remembered old Mr. Lapham, who had died that spring, with more affection than when he had been serving under him. Even Mrs. Lapham now did not seem so bad. Poor woman, how she had struggled and worked for that good, plentiful food, the clean shirts her boys had worn, the scrubbed floors, polished brass! No, she had never been the ogress he had thought her a year ago. There never had been a single day when she had not been the first up in the morning. He, like a child, had thought this was because she liked to get up. Now he realized that there must have been many a day when she was as anxious to lie abed as Dove himself. He remembered when there was no money to buy meat and how she would go from stall to stall until she found a butcher who would accept payment by a new clasp on his pocketbook, or a fishwife who would exchange a basket of salt herrings for a black mourning ring. Her bartering and bickering had then seemed small-minded to him; now he was enough older to realize how valiantly she had fought for those under her care.” (from page 173, Chapter VII. The Fiddler’s Bill)

“Sam Adams said nothing for a moment. He trusted these men about him as he trusted no one else in the world.

‘No. That time is past. I will work for war: the complete freedom of these colonies from any European power. We can have that freedom only by fighting for it. God grant we fight soon. For ten years we’ve tried this and we’ve tried that. We’ve tried to placate them and they to placate us. Gentlemen, you know it has not worked. I will not work for peace. “Peace, peace–and there is no peace.” But I will, in Philadelphia, play a cautious part–not throw all my cards on the table–oh, no. But nevertheless I will work for but one thing. War–bloody and terrible death and destruction. But out of it shall come such a country as was never seen on this earth before. We will fight . .’ (from page 207, Chapter VIII. A World to Come)

Here James Otis interrupts the meeting and speaks to the men:

‘Sammy,’ he said to Sam Adams, ‘my coming interrupted something you were saying…”We will fight,” you had got that far.’

‘Why, yes. That’s no secret.’

For what will we fight?’

‘To free Boston from these infernal redcoats and…’

‘No,’ said Otis. ‘Boy, give me more punch. That’s not enough reason for going into a war. Did any occupied city ever have petter treatment than we’ve had from the British? Has one rebellious newspaper been stopped–one treasonable speech? Where are the firing squads, the jails jammed with political prisoners? What about the gallows for you, Sam Adams, and you, John Hancock? It has neer been set up. I hate those infernal British troops spread all over my town as much as you do. Can’t move these days without stepping on a soldier. But we are not going off into a civil war merely to get them out of Boston. Why are we going to fight? Why, why?’

There was an embarrassed silence. Sam Adams was the acknowledged ringleader. It was for him to speak now.

‘We will fight for the rights of Americans. England cannot take our money away by taxes.’

‘No, no. For something more important than the pocketbooks of our American citizens.’

Rab said, ‘Fo the rights of Englishmen–everywhere.’

‘Why stop with Englishmen?’ Otis was warming up. He had a wide mouth, crooked and generous. He settled back in his chair and then he began to talk. It was such talk as Johnny had never heard before. The words surged up through the bid body, flowed out of the broad mouth. He never raised his voice, and he went on and on. Sometimes Johnny felt so intoxicated by the mere sound of the words that he hardly followed the sense. That soft, low voice flowed over him: submerged him.

‘…For men and women and children all over the world,’ he said. ‘You were right, you tall, dark boy, for even as we shoot down the British soldiers we are fighting for rights such as they will be enjoying a hundred years from now.

‘…There shall be no more tyranny. A handful of men cannot seize power over thousands. A man shall choose who it is shall rule over him.

‘…The peasants of France, the serfs of Russia. Hardly more than animals now. But because we fight, they shall see freedom like a new sun rising in the west. Those natural rights God has given to every man, no matter how humble…’ He smiled suddenly and said ‘…or crazy,’ and took a good pull at his tankard. …

…’James Otis was on his feet, his head close against the rafters that cut down into the attic, making it the shape of a tent. Otis put out his arms.

‘It is all so much simpler than you think,’ he said. He lifted his hands and pushed against the rafters.

‘We give all we have, lives, property, safety, skills…we fight, we die, for a simple thing. Only that a man can stand up.’ (from pages 208-212, Chapter VIII. A World to Come)

‘Mrs. Bessie shook her head, but she wasn’t going to argue any more.

‘How old are you, Johnny?’ she asked.

‘Sixteen.’

‘And what’s that–a boy or a man?’

He laughed. ‘A boy in time of peace and a man in time of war.’ (from page 277, Chapter XI. Yankee Doodle)

The last sentences of the book:

‘True, Rab had died. Hundreds would die, but not the thing they died for.

‘A man can stand up…’ (from page 300, Chapter XII. A Man Can Stand Up)

Loved this book. There were some love interests; Cilla (short for Priscilla), Johnny’s friend throughout his whole time in Boston; she was his age and the Lapham’s daughter; Lavinia Lyte, the extraordinarily beautiful cousin of Johnny, her father (Johnny’s uncle) would not acknowledge Johnny’s right to the family name. This evil Merchant Lyte had Johnny arrested and falsely accused of stealing the silver cup which was his from his mother. They were Tories (loyal to the British) and left Boston for England before the war started.

It was exciting to be in Boston with Johnny Tremain in the 1770s.