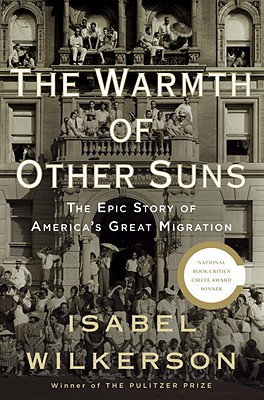

by Isabel Wilkerson, 2010

Fantastic book! Heard about it from Karen, the leader of the Old Town Library Book Club, during our discussion of American Prison. It’s long (550 pages) but gripping and eye-opening. We learn about ‘America’s great migration’ through the true stories of 3 black people who left (really, escaped) the South (Ida Mae from Mississipi in the 1930s, George from Florida in the 1940s, and Robert from Louisiana in the 1950s) and made it to Chicago, New York, and Los Angeles respectively. Their reasons for leaving the South were mainly to get away from the oppressive Jim Crow laws and the threat of death, brutality, oppression everywhere they turned. She describes the injustices they went through and it paints a despicable picture of the American South. From 1870 to 1970 they re-enslaved the African-American and the violence and evil they perpetrated against them is deplorable. God have mercy on us and forgive us.

Unfortunately, what they found after they managed to get out of the South was not much better – although they could sit anywhere and there were no blatant segregation laws, they were kept at the very bottom by discrimination in employment, housing, education, etc. It wasn’t until President Johnson signed the Civil Rights Act in 1964 that things slowly began to change. We’re still needing to change, though, as seen lately by what happened to George Floyd. What a terrible thing we’ve wrought with our evilness.

This book is so well-written, it reads like a novel, as she takes you along with Ida Mae, George, and Bob and tells their life stories. Loved this book!

Here are some eye-opening lines:

“May the Lord be the first one in the car,” she prayed, “and the last one out.” (page 4 describing Ida Mae’s mother, Miss Theenie, and her prayer for her daughter and grandchildren as they escaped the South (Mississipi) in the Jim Crow car of the train.)

Perhaps he might have stayed had they let him practice surgery like he was trained to do or let him walk into the Palace and try on a suit like anyone else of his station. The resentments had grown heavy over the years. He knew he was as smart as anybody else–smarter, to his mind–but he wasn’t allowed to do anything with it, the caste system being what it was. (from page 7 regarding Robert Joseph Pershing Foster, who left Monroe, Louisiana in 1953 and made it to Los Angeles by car. He was a surgeon but was not allowed to practice in any hospital. He made the drive to Los Angeles without being able to get a room in a motel the entire way. He was turned away time after time – that was just one injustice of many in his lifetime.)

The Great Migration, 1915-1970…Over the course of six decades, some six million black southerners left the land of their forefathers and fanned out across the country for an uncertain existence in nearly every other corner of America. The Great Migration would become a turning point in history. It would transform urban America and recast the social and political order of every city it touched. It would force the South to search its soul and finally to lay aside a feudal cast system. It grew out of the unmet promises made after the Civil War and, through the sheer weight of it, helped push the country toward the civil rights revolutions of the 1960s. (from page 9)

The people did not cross the turnstiles of customs at Ellis Island. They were already citizens. But where they came from, they were not treated as such. Their every step was controlled by the meticulous laws of Jim Crow, a nineteenth-century minstrel figure that would become shorthand for the violently enforced codes of the southern caste system. The Jim Crow regime persisted from the 1880s to the 1960s, some eighty years, the average life span of a fairly health man. It afflicted the lives of at least four generations and would not die without bloodshed, as the people who left the South foresaw. …

Its imprint is everywhere in urban life. The configuration of the cities as we know them, the social geography of black and white neighborhoods, the spread of the housing projects as well as the rise of a well-scrubbed black middle class, along with the alternating waves of white flight and suburbanization–all of these grew, directly or indirectly, from the response of everyone touched by the Great Migration. (from pages 9 and 10)

The Great Migration would not end until the 1970s, when the South began finally to change–the whites-only signs came down, the all-white schools opened up, and everyone could vote. By then nearly half of all black Americans–some forty-seven percent–would be living outside the South, compared to ten percent when the Migration began. (from page 10)

The land that colored men managed to get was usually scratch land nobody wanted. (from page 23 describing Ida Mae’s father’s land in Mississippi which flooded every year, the hogs would get stuck, and he dies in 1923 from exposure at the age of 43 after trying to free the hogs.)

She was still grieving when it was time to go back the next fall. She walked a mile of dirt road past the drying cotton and the hackberry trees to get to the one-room schoolhouse that, one way or the other, had to suffice for every colored child from first to eighth grade, the highest you could go back then if you were colored in Chickasaw County. (from pages 24 and 25)

For all its upheaval, the Civil War had left most blacks in the South no better off economically than they had been before. Sharecropping, slavery’s replacement, kept them in debt and still bound to whatever plantation they worked. But one thing had changed. The federal government had taken over the affairs of the South, during a period known as Reconstruction, and the newly freed men were able to exercise rights previously denied them. They could vote, marry, or go to school if there were one nearby, and the more ambitious among them could enroll in black colleges set up by northern philanthropists, open businesses, and run for office under the protection of northern troops. In short order, some managed to become physicians, legislators, undertakers, insurance men. They assumed that the question of black citizen’s rights had been settled for good and that all that confronted them was merely building on these new opportunities.

But, by the mid-1870s, when the North withdrew its oversight in the face of southern hostility, whites in the South began to resurrect the caste system founded under slavery. Nursing the wounds of defeat and seeking a scapegoat, much like Germany in the years leading up to Nazism, they began to undo the opportunities accorded freed slaves during Reconstruction and to refine the language of white supremacy. They would create a caste system based not on pedigree and title, as in Europe, but solely on race, and which, by law, disallowed any movement of the lowest caste into the mainstream. (from pages 37 and 38)

The South began acting in outright defiance of the Fourteenth Amendment of 1868, which granted the right to due process and equal protection to anyone born in the United States, and it ignored the Fifteenth Amendment of 1880, which guaranteed all men the right to vote.

Politicians began riding these anti-black sentiments all the way to governors’ mansions throughout the South and to seats in the U.S. Senate.

“If it is necessary, every Negro in the state will be lynched,” James K. Vardaman, the white supremacy candidate in the 1903 Mississippi governor’s race, declared. He saw no reason for blacks to go to school. “The only effect of Negro education,” he said, “is to spoil a good field hand and make an insolent cook.”

Mississippi voted Vardaman into the governor’s office and later sent him to the US. Senate.

…In spectacles that often went on for hours, black men and women were routinely tortured and mutilated, then hanged or burned alive, all before festive crowds of as many as several thousand white citizens, children in tow, hoisted on their fathers’ shoulders to get a better view.

…Across the South, someone was hanged or burned alive every four days from 1889 to 1929, according to the 1933 book The Tragedy of Lynching…

…wrote the historian Herbert Shapiro. “All blacks lived with the reality that no black individual was completely safe from lynching.” (from pages 38 and 39)

It was during that time, around the turn of the twentieth century, that southern state legislatures began devising with inventiveness and precision laws that would regulate every aspect of black people’s lives, solidify the southern caste system, and prohibit even the most casual and incidental contact between the races.

They would come to be called Jim Crow laws. It is unknown precisely who Jim Crow was or if someone by that name actually existed.

…All told, these statues only served to worsen race relations, alienating one group from the other and removing the few informal interactions that might have helped both sides see the potential good and humanity in the other. (from pages 40, 41, 42)

These were the facts of their lives–of Ida Mae’s, George’s, and Pershing’s existence before they left–carried out with soul-killing efficiency until Jim Crow expired under the weight of the South’s own sectarian violence: bombings, hosing of children, and the killing of dissidents seeking basic human rights. Jim Crow would not get a proper burial until the enactment of federal legislation, the Civil Rights Act of 1964, which was nonetheless resisted years after its passage as vigorously as Reconstruction had been and would not fully take hold in many parts of the South until well into the 1970s. (from page 45)

The arbitrary nature of grown people’s wrath gave colored children practice for life in the caste system, which is why parents, forced to train their children in the ways of subservience, treated their children as the white people running things treated them. It was preparation for the lower-caste role children were expected to have mastered by puberty. (from pages 49 and 50)

Thereafter, Florida continued to live up to its position as the southernmost state with among the most heinous acts of terrorism committed anywhere in the South. Violence had become such and accepted fact of life that, in 1950,the Florida governor’s special investigator, Jefferson Elliott, observed that there had been so many mob executions in one county that it “never had a negro live long enough to go to trial.”

..Surrounded as he was by the arbitrary violence of he ruling caste, it would be nearly impossible for George or any other colored boy in that era to grow u without the fear of being lynched, the dread that, in the words of the historian James R. McGovern, “he might be accused of something and suddenly find himself in a circle of tormentors with no one to help him.” (from page 62)

As for Lil George, no colleges near Eustis nor any state universities in Florida, for that matter, admitted colored students. The closest colored colleges were hours away. (from page 71)

…He knew there was a dividing line, but it was hitting him in the face now. He was showing a talent for science and was getting to the point that he needed reference books to do his lesson. But it was against the law for colored people to go the public library. …

He was in the eighth grade when word filtered to his side of the tracks that Monroe was getting a new high school. It wouldn’t replace the old buiding that Monroe Colored High was in. It was for the white students, who already had a big school. …

As the new high school took shape across town, Pershing watched his father rise in the black of morning to milk the cows and walk the mile and a half to open his building the size of a grade school. His father, his mother, and the other teachers at Monroe Colored High School were working long hours with hand-me-down supplies for a fraction of the pay their white counterparts were getting. …

The disparity in pay, reported without apology in the local papers for all to see, would have far-reaching effects. It would mean that even the most promising of colored people, having received next to nothing in material assets from their slave foreparents, had to labor with the knowledge that they were now being underpaid by more than half, that they were so behind it would be all but impossible to accumulate the assets their white counterparts could, and that they would, by definition, have less to leave succeeding generations than similar white families…The layers of accumulated assets built up by the better-paid dominant caste, generation after generation, would factor into a wealth disparity of white Americans having an average net worth ten times that of black Americans by the turn of the twenty-first century, dampening the economic prospects of the children and grandchildren of both Jim Crow and the Great Migration before they were even born.

…”The money allocated to the colored children is spent on the education of the white children,” a local school superintendent in Louisiana said bluntly. “We have twice as many colored children of school age as we have white, and we use their money. Colored children are mighty profitable to us.” (from pages 84-86)

She said she would try, but there was no use pretending. She was not going to be of much help in the field. She had never been ale to pick a hundred pounds. One hundred was the magic number. It was the benchmark for payment when day pickers took to the field, fifty cents for a hundred pounds of cotton in the 1920s, the gold standard of cotton picking.

It was like picking a hundred pounds of feathers, a hundred pounds of lint dust. It was “one of the most backbreaking forms of stoop labor ever known,” wrote the historian Donald Holley. It took some seventy bolls to make a single pound of cotton, which meant Ida Mae would have to pick seven thousand bolls to reach a hundred pounds. It meant reaching past the branches into the cotton flower and pulling a soft lock of cotton the size of a walnut out of its pod, doing this seven thousand times and turning around and doing the same thing the next day and the day after that.

…The work was not so much hazardous as it was mind-numbing and endless, requiring them to pick from the moment the sun peeked over the tree line to the moment it fell behind the horizon and they could no longer see. After ten or twelve hours, the pickers could barely stand up straight for all the stooping. (from page 97)

The southern colonel had no assignment for him, so Pershing had no choice but to wait until the following week. When he returned, he learned there would be no leadership position for him. A white officer would be chief of surgery, as it had always peen. Pershing would have no title other than staff doctor. Jim Crow had followed him across the Atlantic, and it was hitting him that he would never get ahead as long as these apostles of Jim Crow were over him. (from page 146)

George went to Mr. Edd first thing in the morning to find out what happened and wherehis cousin was and to register his discontent. Ida Mae didn’t want him going in the state of mind he was in and told him to mind his words. He had to walk a thin line between being a man and acting a slave. Step too far on one side, and he couldn’t live with himself. Step too far on the other, and he might not live at all.

…Joe Lee survived the night. The boss man told George to go get him at the jail. George, Willie, Saint, and the other colored men on the plantation took grease to peel the overalls off him, just as their slave forefathers had done after whippings generations before. They carried Joe Lee back to his father’s farm in the fresh clothes they put on him, and the people went back to picking cotton. The lash wounds on Joe Lee’s back healed in time. But Joe Lee was never right again, people said. And, in a way, neither was George. (from page 149)

In the months that George had been rousing up the pickers, their world had grown even more dangerous due to the state’s desperate wartime need for labor. From the panhandle to the Everglades, Florida authorities were now arresting colored men off the street and in their homes if they were caught not working. Charged with vagrancy, the men were assessed fines of several weeks’ pay and made to pick fruit or cut sugarcane to work off the debt if they did not have the money, which few of them did and as the authorities fully anticipated. Those captured were hauled to remote plantations or turpentine camps, held by force, and beaten or shot if they tried to escape.

It was an illegal form of contemporary slavery called debt peonage, which persisted in Florida, Georgia, Alabama, and other parts of the Deep South well into the 1940s. (from page 152)

But the masses did not pour out of the South until they had something to go to. They got their chance when the North began courting them, hard and in secret, in the face of southern hostility, during the labor crisis of World War I. Word had spread like wildfire that the North was finally “opening up.”

The war had cut the supply of European workers the North had relied on to kill its hogs and stoke its foundries. Immigration plunged by more than ninety percent, from 1,218,480 in 1914 to 110,618 in 1918, when the country needed all the labor it could get for war production. So the North turned its gaze to the poorest-paid labor in the emerging market of the American South. Steel mills, railroads, and packinghouses sent labor scouts disguised as insurance men and salesmen to recruit blacks north, if only temporarily.

The recruiters would stride through groupings of colored people and whisper without stopping, “Anybody want to go to Chicago, see me.” It was an invitation that tapped into pent-up yearnings and was just what the masses had been waiting for. (from page 161)

At first the South was proud and ambivalent, pretended that it did not care. “As the North grows blacker, the South grows whiter,” the New Orleans Times-Picayune happily noted.

Then, as planters awoke to empty fields, the South began to panic. “Where shall we get labor to take their places?” asked the Montgomery Advertiser, as southerners began to confront the reality observed by the Columbia State of South Carolina: “Black labor is the best labor the South can get. No other would work long under the same conditions.”

“It is the life of the South,” a Georgia plantation owner once said. “It is the foundation of its prosperity. . . . God pity the day when the negro leaves the South.” (from page 162)

When the people kept leaving, the South resorted to coercion and interception worthy of the Soviet Union, which was forming at the same time across the Atlantic. Those trying to leave were rendered fugitives by definition and could not be certain they would be able to make it out. In Brookhaven, Mississippi, authorities stopped a train with fifty colored migrants on it and sidetracked it for three days. In Albany, Georgia, the police tore up the tickets of colored passengers as they stood waiting to board, dashing their hopes of escape. A minister in South Carolina, having seen his parishioners off, was arrested at the station on the charge of helping colored people get out. In Savannah, Georgia, the police arrested every colored person at the station regardless of where he or she was going. In Summit, Mississippi, authorities simply closed the ticket office and did not let northbound trains stop for the colored people waiting to get on. (from page 163)

The Rooming house in Lordsburg was part of a haphazard network of twentieth-century safe houses that sprang up all over the country, and particularly in the South, during the decades of segregation. Some were seedy motels in the red-light district of whatever city they were in. There were a handful of swanky ones, like the Hotel Theresa in Harlem. But many of them were unkempt rooming houses or merely an extra bedroom in some colored family’s row house in the colored district of a given town. They sprang up out of necessity as the Great Migration created a need for places where colored people could stop and rest in a world where no hotels in the South accepted colored people and those in the North and West were mercurial in their policies, many of them disallowing blacks as readily as hotels in the South.

Thus, there developed a kind of underground railroad for colored travelers, spread by word of mouth among friends and in fold-up maps and green paperback guidebooks that listed colored lodgings by state or city. (from page 263)

Th Great Migration forced Harlem property owners to make a choice. They could try to maintain a whites-only policy in a market being deserted by whites and lose everything, or they could take advantage of the rising black demand and “rent to colored people at higher prices and survive,” Osofsky wrote. Most were pragmatic and did the latter. (from page 250)

The boy’s first day of school in the North, he was assigned to a grade lower than the one he’d been in where he had come from, and the teacher couldn’t understand his southern accent. When she asked him his name, he said he was called J.C. The teacher misheard him and, from that day forward, called him Jesse instead. So did everyone else in this new world he was in. He would forever be known as Jesse Owens, not by his given name. He would go on to win four gold medals at the 1936 Olympics in Berlin, becoming the first American in the history of track and field to do so in a single Olympics and disproving the Aryan notions of his Nazi hosts.

It made headlines throughout the United States that Adolf Hitler, who had watched the races, had refused to shake hands with Owens, as he had with white medalists. But Owens found that in Nazi Germany, he had been able to stay in the same quarters and eat with his white teammates, something he could not do in his home country. Upon his return, there was a ticker-tape parade in New York. Afterward, he was forced to ride the freight elevator to his own reception at the Waldorf-Astoria.

“I wasn’t invited to shake hands with Hitler,” he wrote in his autobiography. “But I wasn’t invited to the White House to shake hands with the President either. I came back to my native country, and I could not ride in the front of the bus. I had to go to the back door. I couldn’t live where I wanted. Now, what’s the difference?” (from page 266)

Contrary to modern-day assumptions, for much of the history of the United States–from the Draft Riots of the 1860s to the violence over desegregation a century later–riots were often carried out by disaffected whites against groups perceived as threats to their survival. Thus riots would become to the North what lynchings were to the South, each a display of uncontained rage by put-upon people directed toward the scapegoats of their condition. Nearly every big northern city experienced one or more during the twentieth century. (from page 273)

And more and more that I do not have time to document here. This was an eye-opening book! I learned so much. It needs to be required reading for all high school students in America. It is a crime that we were not taught this. This is a beautifully written and necessary book.