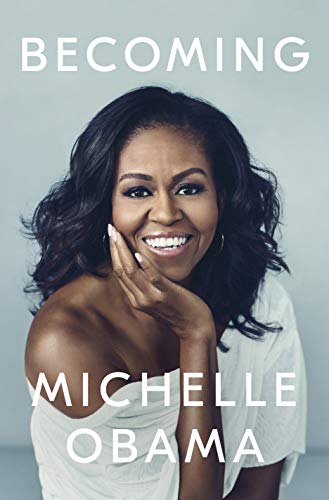

by Michelle Obama, 2018

Wonderful book by and about Michelle Obama, her growing up years in the South Side of Chicago, her college years at Princeton and Harvard Law School, her meeting and falling in love with Barack Obama when he was a summer intern at the law firm where she worked, her marriage to him in October of 1992, their difficulty conceiving and finally having 2 precious girls via IVF (Malia in 1998 and Sasha in 2001), Barack’s desire to run for Illinois State Senate, then U.S. Senate, then President – she never wanted him to have a life in politics but he wanted to change the world and did; then their 8 years in the White House, and lastly, the traumatic and painful 2016 election and turning over the White House to Donald Trump. A very personal and intimate journey into the life of an extraordinary woman. Thank you, Michelle Obama, for writing this book.

Here are some quotes from the book:

Craig, for example, got a new bike one summer and rode it east to Lake Michigan, to the paved pathway along Rainbow Beach, where you could feel the breeze off the water. He’d been promptly picked up by a police officer who accused him of stealing it, unwilling to accept that a young black boy would have come across a new bike in an honest way. (The officer, an African American man himself, ultimately got a brutal tongue-lashing from my mother, who made him apologize to Craig.) What had happened, my parents told us, was unjust but also unfortunately common. The color of our skin made us vulnerable. It was a thing we’d always have to navigate.

from page 25

These were highly intelligent, able-bodied men who were denied access to stable high-paying jobs, which in turn kept them from being able to buy homes, send their kids to college, or save for retirement.

From pages 38 and 39 describing her great-grandfather, great-uncle, grandfather, uncle not being able to get union cards due to discrimination in order to become electricians, plumbers, carpenters, even taxi-drivers, so having to settle on lower paying jobs.

No matter how hard we tried, we couldn’t seem to come up with a pregnancy…We had one pregnancy test come back positive, which caused us both to forget every worry and swoon with joy, but a couple of weeks later I had a miscarriage, which left me physically uncomfortable and cratered any optimism we’d felt. Seeing women and their children walking happily along a street, I’d feel a pang of longing followed by a bruising wallop of inadequacy…It was maybe then that I felt a first flicker of resentment involving politics and Barack’s unshakable commitment to the work. Or maybe I was just feeling the acute burden of being female…I walked around with a secret inside me. This was my privilege, the gift of being female. I felt bright with the promise of what I carried.

From pages 187 – 190 describing their difficulties trying to get pregnant, eventually succeeding via IVF.

When I was in first grade, a boy in my class punched me in the face one day, his fist coming like a comet, full force and out of nowhere…The boy got a talking-to from our teacher. My mother went over to school to personally lay eyes on the kid, wanting to assess what kind of threat he posed…”That boy was just scared and angry about things that had nothing to do with you,” my mother told me later in our kitchen as she stirred dinner on the stove. She shook her head as if to suggest she knew more than she was willing to share. “He’s dealing with a whole lot of problems of his own.”…According to my mother, who would probably want some sort of live-and-let-live slogan carved on her headstone, the key was never to let a bully’s insults or aggression get to you personally.

If you did–well, then, you could really get hurt.

From pages 250-251 where she is describing the campaign for the Presidency in 2008

I’d been in Wisconsin one day in February when Katie got a call from someone on Barack’s communications team, saying that there seemed to be a problem. I’d evidently said something controversial in a speech I’d given at a theater in Milwaukee a few hours earlier…

Later that day, we saw the issue for ourselves. Someone had taken film from my roughly forty-minute talk and edited it down to a single ten-second clip, stripping away the context, putting the emphasis on a few words.

…The fuller version of what I’d said that day went like this: “What we’ve learned over this year is that hope is making a comeback! And let me tell you something, for the first time in my adult lifetime, I’m really proud of my country. Not just because Barack has done well, but because I think people are hungry for change. I have been desperate to see our country moving in that direction, and just not feeling so alone in my frustration and disappointment. I’ve seen people who are hungry to be unified around some basic common issues, and it’s made me proud. I feel privileged to be a part of even witnessing this.”

But nearly all of that had been peeled back, including my references to hope and unity and how moved I was. The nuance was gone; the gaze directed toward one thing. What was in the clips–and now sliding into heavy rotation on conservative radio and TV talk shows, we were told–was this: “For the first time in my adult lifetime, I’m really proud of my country.”

I didn’t need to watch the news to know how it was being spun. She’s not a patriot. She’s always hated America. This is who she really is. The rest is just a show.

Here was the first punch. And I’d seemingly brought it on myself. In trying to speak casually, I’d forgotten how weighted each little phrase could be. Unwittingly, I’d given the haters a fourteen-word feast. Just like in first grade, I hadn’t seen it coming.

From pages 259- 260 where she is describing her speeches in Madison and Milwaukee and how the conservative press used one of her phrases against her

And yet a pernicious seed had been planted–a perception of me as disgruntled and vaguely hostile, lacking some expected level of grace. Whether it was originating fro Brack’s political opponents or elsewhere, we couldn’t tell, but the rumors and slanted commentary almost always carried less-than-sublte messaging about race, meant to stir up the deepest and ugliest kind of fear within the voting public. Don’t let the black folks take over. They’re not like you. Their vision is not yours.

This wasn’t helped by the fact that ABC News had combed through twenty-nine hours of the Reverend Jeremiah Wright’s sermons, splicing together a jarring highlight reel that showed the preacher careening through callous and inappropriate fits of rage and resentment at white America, as if white people were to blame for every woe. Barack and I were dismayed to see this, a reflection of the worst and most paranoid parts of the man who’d married us and baptized our children.

From page 262

…The message seemed often to get telegraphed, if never said directly: These people don’t belong. A photo of Barack wearing a turban and traditional Somali clothing that had been bestowed on him during an official visit to Kenya as a senator had shown up on the Drudge Report, reviving old theories that he was secretly Muslim. A few months later, the internet would burp up another anonymous and unfounded rumor, this one questioning Barack’s citizenship, floating the idea that he’d been born not in Hawaii but in Kenya, which would make him ineligible to become president.

…I was getting worn out, not physically, but emotionally. The punches hurt, even if I understood that they had little to do with who I really was as a person. It was is if there were some cartoon version of me out there wreaking havoc, a woman I kept hearing about but didn’t know–a too-tall, too-forceful, ready-to-emasculate Godzilla of a political wife named Michelle Obama…

…NPR’s website carried a story with the headline: “Is Michelle Obama an Asset or Liability?” Below it, in boldface, came what were apparently point of debate about me: “Refreshingly Honest or Too Direct?” and “Her Looks: Regal or Intimidating?”

I am telling you, this stuff hurt.

From pages 264 and 265 describing the campaign for the presidency and how the media twists everything.

My husband’s career had allowed me to witness the machinations of politics and power up close. I’d seen how just a handful of votes in every precinct could mean the difference not just between one candidate and another but between one value system and the next. If a few people stayed home in each neighborhood, it could determine what our kids learned in schools, which health-care options we had available, or whether or not we sent our troops to war. Voting was both simple and incredibly effective.

From page 274

…It’s a huge place, the White House, with 132 rooms, 35 bathrooms, and 28 fireplaces spread out over six floors, all of it stuffed with more history than any single tour could begin to cover…

…President and Mrs. Bush greeted us at the Diplomatic Reception Room, just off the South Lawn. The First Lady clasped my hand warmly. “Please call me Laura,” she said. Her husband was just as welcoming, possessing a magnanimous Texas spirit that seemed to override any political hard feelings. Throughout the campaign, Barack had criticized the president’s leadership frequently and in detail, promising voters he would fix the many things he viewed as mistakes. Bush, as a Republican, had naturally supported John McCain’s candidacy. But he’d also vowed to make this the smoothest presidential transition in history, instructing every department in the executive branch to prepare briefing binders for the incoming administration. Even on the First Lady’s side, staffers were putting together contact lists, calendars, and sample correspondence to help me find my footing when it came to the social obligations that came with the title. There was kindness running beneath all of it, a genuine love of country that I will always appreciate and admire.

From page 289 when the Obama’s move into the White House

The president-elect, I learned, is given access to $100,000 in federal funds to help with moving and redecorating, but Barack insisted that we pay for everything ourselves, using what we’d saved from his book royalties. As long as I’ve known him, he’s been this way: extra-vigilant when it comes to matters of money and ethics, holding himself to a higher standard than even what’s dictated by law.

Page 294

My mother would end up staying with us in Washington for the next eight years, but at the time she claimed the move was temporary, that she’d stay only until the girls got settled. She also refused to get put into any bubble. She declined Secret Service protection and avoided the media in order to keep her profile low and her footprint light. She’d charm the white House housekeeping staff by insisting on doing her own laundry, and for years to come, she’d slip in and out of the residence as she pleased, walking out the gates and over to the nearest CVS or Filene’s Basement when she needed something, making new friends and meeting them out regularly for lunch. Anytime a stranger commented that she looked exactly like Michelle Obama’s mother, she’d just give a polite shrug and say, “Yeah, I get that a lot,” before carrying on with her business. As she always had, my other did things her own way.

Page 296

People ask what it’s like to live in the White House. I sometimes say that it’s a bit like what I imagine living in a fancy hotel might be like, only the fancy hotel has no other guests in it–just you and your family. There are fresh flowers everywhere, with new ones brought in almost every day. The building itself feels old and a little intimidating. The walls are so thick and the planking on the floors so solid that sound in the residence seems to get absorbed quickly. The windows are grand and tall and also fitted with bomb-resistant glass, kept shut at all times for security reasons, which further adds to the stillness.

Page 304

I understood how lucky we were to be living this way. the master suite in the residence was bigger than the entirety of the upstairs apartment my family had shared when I was rowing up on Euclid Avenue. There was a Monet painting hanging outside my bedroom door and a bronze Degas sculpture in our dining room. I was a child of the South Side, now raising daughters who slept in rooms designed by a high-end interior decorator and who could custom order their breakfast from a chef.

Page 305

For the first few months in the White House, I felt the need to be watchful over everything. One of my earliest lessons was that it could be relatively costly to live there. While we stayed rent-free in the residence and had our utilities and staffing paid for, we nonetheless covered all other living expenses, which seemed to add up quickly, especially given the fancy-hotel quality of everything. We got an itemized bill each month for every food item and roll of toilet paper. We paid for every guest who came for an overnight stay or joined us for a meal. And with a culinary staff that had Michelin-level standards and a deep eagerness to please the president, I had to keep an eye on what got served. When Barack offhandedly remarked that he liked the taste of some exotic fruit at breakfast or the sushi on his dinner plate, the kitchen staff took note and put them into regular rotation on the menu. Only later, inspecting the bill, would we realize that some of these items were being flown in at great expense from overseas.

Page 307-308

…Weeks earlier, before the inauguration, the conservative radio host Rush Limbaugh baldly announced, “I hope Obama fails.” I’d watched with dismay as Republicans in Congress followed suit, fighting Barack’s every effort to stanch the economic crisis, refusing to support measures that would cut taxes and save or create millions of jobs.

Page 311

…If anyone in our family wanted to step outside onto the Truman Balcony–the lovely arcing terrace that overlooked the South Lawn, and the only semiprivate outdoor space we had at the White House–we needed to first alert the Secret Service so that they could shut down the section of E Street that was in view of the balcony, clearing out the flocks of tourists who gathered there at all hours of the day and night. There were many times when I thought I’d go out to sit on the balcony, but then reconsidered, realizing the hassle I would cause, the vacations I’d be interrupting, all because I thought it would be nice to have a cup of tea outdoors.

Pages 325-326

As we flew back to Washington late that night, I already knew it would be a long time before we did anything like this again. Barack’s political opponents would criticize him for taking me to New York to see a show. The Republican Party would put out a press release before we’d even gotten home, saying that our date had been extravagant and costly to taxpayers, a message that would be picked up and debated on cable news….

…The harder part was seeing the selfishness inherent in making that choice, knowing that it had required hours of advance meetings between security teams and local police. It had involved extra work for our staffers, for the theater, for the waiters at the restaurant, for the people whose cars had been diverted off Sixth Avenue, for the police on the street…

Page 327

…I turned back toward the lawn, horrified to see my family being chased by wild animals and the wild animals being chased by agents, who were firing their guns.

“This is your plan?” I screamed. “Are you kidding me?”

Just then, the cheetah let out a snarl and launched itself at Sasha, its claws extended, its body seeming to fly. An agent took a shot, missing the animal though scaring it enough that it veered off course and retreated back down the hill. I was relieved for a split second, but then I saw it–a white-and orange tranquilizer dart lodged in Sash’s right arm.

I lurched upward in bed, heart hammering, my body soaked in sweat, only to find my husband curled in comfortable sleep beside me. I’d had a very bad dream.

Page 341 describing her nightmare of a man named Lloyd who brought 4 wild cats to the White House lawn, roaming free, for them to see and pet and the animals were supposedly tranquilized but then attacked

…He’d be blamed for things he couldn’t control, pushed to solve frightening problems in faraway nations, expected to plug a hole at the bottom of the ocean. His job, it seemed, was to take the chaos and metabolize it somehow into calm leadership–every day of the week, every week of the year.

Page 342

The issues I was working on weren’t simple, but still they were manageable in ways that much of what kept my husband at his desk at night was not. As had been the case since I first met him, nighttime was when Barack’s mind traveled without distraction. It was during these quiet hours that he could find perspective or inhale new information, adding data points to the vast mental map he carried around. Ushers often came to the Treaty Room a few times over the course of an evening to deliver more folders, containing more papers, freshly generated by staffers who were working late in the offices downstairs. If Barack got hungry, a valet would bring him a small dish of figs or nuts. He was no longer smoking, thankfully, though he’d often chew a piece of nicotine gum. Most nights of the week, he stayed at his desk until 1:00 or 2:00 in the morning, reading memos, rewriting speeches, and responding to email while ESPN played low on the TV. He always took a break to come kiss me and the girls good night.

I was used to it by now–his devotion to the never-finished task of governing. For years, the girls and I had shared Barack with his constituents, and now there were more than 300 million of them. Leaving him alone in the Treaty Room at night, I wondered sometimes if they had any sense of how lucky they were.

The last bit of work he did, usually at some hour past midnight, was to read letters from American citizens. Since the start of his presidency, Barack had asked his correspondence staff to include ten letters or messages from constituents inside his briefing book, selected from the roughly fifteen thousand letters and emails that poured in daily. He read each one carefully, jotting responses in the margins so that a staffer could prepare a reply or forward a concern on to a cabinet secretary. …

He read all of it, seeing it as part of the responsibility that came with the oath. He had a hard and lonely job–the hardest and loneliest in the world, it often seemed to me–but he knew that he had an obligation to stay open, to shut nothing out. While the rest of us slept, he took down the fences and let everything inside.

Pages 349 and 350

…”We’re praying nobody hurts you,” people used to say, clasping my hand at campaign events. I’d heard it from people of all races, all backgrounds, all ages–a reminder of the goodness and generosity that existed in our country. “We pray for you and your family every day.”

I kept their words with me. I felt the protection of those millions of decent people who prayed for our safety. Barack and I both relied on our personal faith as well. We went to church only rarely now, mostly because it had become such a spectacle, involving reporters shouting questions as we walked in to worship. Ever since the scrutiny of the Revered Jeremiah Wright had become an issue in Barack’s first presidential campaign, ever since opponents had tried to use faith as a weapon–suggesting that Barack was a “secret Muslim”–we’d made the choice to exercise our faith privately and at home, including praying each night before dinner and organizing a few sessions of Sunday school at the White House for our daughters. We didn’t join a church in Washington, because we didn’t want to subject another congregation to the kind of bad-faith attacks that had rained down on Trinity, our church in Chicago. It was a sacrifice, though. I missed the warmth of a spiritual community. Every night, I’d look over and see Barack lying with his eyes closed on the other side of the bed, quietly saying his prayers.

Page 353

Over the course of the winter of 2011, we’d been hearing news that the reality-show host and New York real-estate developer Donald Trump was beginning to make noise about possibly running for the Republican presidential nomination when Barack came up for reelection in 2012. Mostly though, it seemed he was just making noise in general, surfacing on cable shows to offer yammering, inexpert critiques of Barack’s foreign policy decisions and openly questioning whether he was an American citizen. The so-called birthers had tried during the previous campaign to feed a conspiracy theory claiming that Barack’s Hawaiian birth certificate was somehow a hoax and that he’d in fact been born in Kenya. Trump was now actively working to revive the argument, making increasingly outlandish claims on television, insisting that the 1961 Honolulu newspaper announcements of Barack’s birth were fraudulent and that none of his kindergarten classmates remembered him. All the while, in their quest for clicks and ratings, news outlets–particularly the more conservative ones–were gleefully pumping oxygen into his groundless claims.

The whole thing was crazy and mean-spirited, of course, its underlying bigotry and xenophobia hardly concealed. But it was also dangerous, deliberately meant to stir up the wingnuts and kooks. I feared the reaction. I was briefed from time to time by the Secret Service on the more serious threats that came in and understood that there were people capable of being stirred. I tried not to worry, but sometimes I couldn’t help it. What if someone with an unstable mind loaded a gun and drove to Washington? What if that person went looking for our girls? Donald Trump, with his loud and reckless innuendos, was putting my family’s safety at risk. And for this, Id never forgive him.

Pages 352-353

On the first Sunday in May 2011, I went to dinner with two friends at a restaurant downtown, leaving Barack and my mother in charge of the girls at home. The weekend had seemed especially busy. Barack had been pulled into a flurry of briefings that afternoon, and we’d spent Saturday evening at the White House Correspondents’ Dinner, where in his speech Barack made a few pointed jokes about Donald Trump’s Celebrity Apprentice career and his birther theories. I couldn’t see him from my seat, but Trump had been in attendance. During Barack’s monologue, news cameras zeroed in on him, stone-faced and stewing.

Pages 362-363

Mandela had gone to jail for his principles. He’d missed seeing his kids grow up, and then he’d missed seeing many of his grandkids grow up, too. All this without bitterness. All this still believing that the better nature of his country would at some point prevail. He’d worked and waited, tolerant and undiscouraged, to see it happen.

I flew home propleed by that spirit. Life was teaching me that progress and change happen slowly. Not in two years, four years, or even a lifetime. We were planting seeds of change, the fruit of which we might never see. We had to be patient.

Three times over the course of the fall of 2011, Barack proposed bills that would create thousands of jobs for Americans, in part by giving states money to hire more teachers and first responders. Three times the Republicans blocked them, never even allowing a vote.

…The Republican Congress was devoted to Barack’s failure above all else.

Page 370

…”Eighty degrees and sunny!” Everyone in the circle began nodding, ruefully. I wasn’t sure why. “Tell Mrs. Obama,” she said. “What goes through your mind when you wake up in the morning and hear the weather forecast is eighty and sunny?”

She clearly knew the answer, but wanted me to hear it.

A day like that, the Harper students all agreed, was no good. When the weather was nice, the gangs got more active and the shooting got worse.

These kids had adapted to the upside-down logic dictated by their environment, staying indoors when the weather was good, varying the routes they took to and from school each day based on shifting gang territories and allegiances. Sometimes, they told me, taking the safest path home meant walking right down the middle of the street as cars sped past them on both sides. Doing so gave them a better view of any escalating fights or possible shooters. And it gave them more time to run.

From page 386 where she is visiting a group of Harper High School students in Chicago

“Honestly,” I began, “I know you’re dealing with a lot here, but no one’s going to save you anytime soon. Most people in Washington aren’t even trying. A lot of them don’t even know you exist.” I explained to those students that progress is slow, that they couldn’t afford to simply sit and wait for change to come. Many Americans didn’t want their taxes raised, and Congress couldn’t even pass a budget let alone rise above petty partisan bickering, so there weren’t going to be billion-dollar investments in education or magical turnarounds for their community. Even after the horror of Newtown, Congress appeared determined to block any measure that could help keep guns out of the wrong hands, with legislators more interested in collecting campaign donations from the National Rifle Association then they were in protecting kids. Politics was a mess, I said. On this front, I had nothing terribly uplifting or encouraging to say.

I went on, though, to make a different pitch, one that came directly from my South Side self. Use school, I said.

These kids had just spent an hour telling me stories that were tragic and unsettling, but I reminded them that those same stories also showed their persistence, self-reliance, and ability to overcome. I assured them that they already had what it would take to succeed. Here they were, sitting in a school that was offering them a free education, I said, and there were a whole lot of committed and caring adults inside that school who thought they mattered. About six weeks later, thanks to donations from local businesspeople, a group of Harper students would come to the White House, to visit with me and Barack personally, and also spend time at Howard University, learning what college was about. I hoped that they could see themselves getting there.

Page 387

A year and a half after Newtown, Congress had passed not a single gun-control measure. Bin Laden was gone, but ISIS had arrived. The homicide rate in Chicago was going up rather than down. A black teen named Michael Brown was shot by a cop in Ferguson, Missouri, his body left in the middle of the road for hours. A black teen named Laquan McDonald was shot sixteen times by police in Chicago, including nine times in the back. A black boy named Tamir Rice was shot dead by police in Cleveland while playing with a toy gun. A black man named Freddie Gray dies after being neglected in police custody in Baltimore. a black man named Eric Garner was killed by police after being put in a choke hold during his arrest on Staten Island. All this was evidence of something pernicious and unchanging in America. When Barack was first elected, various commentators had naively declared that our country was entering a “postracial” era, in which skin color would no longer matter. Here was proof of how wrong they’d been. As Americans obsessed over the threat of terrorism, many were overlooking the racism and tribalism that were tearing our nation apart.

Lat in June 2015, Barack and I flew to Charleston, South Carolina, to sit with another grieving community–this time at the funeral of a pastor named Clementa Pinckney, who had been one of nine people killed in a racially motivated shooting earlier in the month at an African Methodist Episcopal church known simply as Mother Emanuel. The victims, all African Americans, had welcomed an unemployed twenty-one-year-old white man–a stranger to them all–into their Bible study group. He’d sat with them for a while; then, after the group bowed their heads in prayer, he stood up and began shooting. In the middle of it, he was reported to have said, “I have to do this, because you rape our women and you’re taking over our country.”

After delivering a moving eulogy for Reverend Pinckney and acknowledging the deep tragedy of the moment, Barack surprised everyone by leading the congregation in a slow and soulful rendition of “Amazing Grace.” It was a simple invocation of hope, a call to persist. Everyone in the room, it seemed, joined in. For more than six years now, Barack and I had lived with an awareness that we ourselves were a provocation. As minorities across the country were gradually beginning to take on more significant roles in politics, business, and entertainment, our family had become the most prominent example. Our presence in the White House had been celebrated by millions of Americans, but it also contributed to a reactionary sense of fear and resentment among others. The hatred was old and deep and as dangerous as ever.

Pages 396-397

I tried to communicate the one message about myself and my staton in the world that I felt might really mean something. Which was that I knew invisibility. I’d lived invisibility. I came from a history of invisibility. I liked to mention that I was the great-great-granddaughter of a slave named Jim Robinson, who was probably buried in an unmarked grave somewhere on a South Carolina plantation. And in standing at a lectern in front of students who were thinking about the future, I offered testament to the idea that it was possible, at least in some ways, to overcome invisibility.

Page 405

Since childhood, I’d believed it was important to speak out against bullies while also not stooping to their level. and to be clear, we were now up against a bully, a man who among other things demeaned minorities and expressed contempt for prisoners of war, challenging the dignity of our country with practically his every utterance. I wanted Americans to understand that words matter–that the hateful language they heard coming from their TVs did not reflect the true spirit of our country and that we could vote against it. It was dignity I wanted to make an appeal for–the idea that as a nation we might hold on to the core thing that had sustained my family, going back generations. Dignity had always gotten us through. It was a choice, and not always the easy one, but the people I respected most in life made it again and again, every single day. There was a motto Barack and I tried to live by, and I offered it that night from the stage: When they go low, we go high.

Two months later, just weeks before the election, a tape would surface of Donald Trump in an unguarded moment, bragging to a TV host in 2005 about sexually assaulting women, using language so lewd and vulgar that it put media outlets in a quandary about how to quote it without violating the established standards of decency. In the end, the standards of decency were simply lowered in order to make room for the candidate’s voice.

When I heard it, I could hardly believe it. And then again, there was something painfully familiar in the menace and male jocularity of that tape. I can hurt you and get away with it. It was an expression of hared that had generally been kept out of polite company, but still lived in the marrow of our supposedly enlightened society–alive and accepted enough that someone like Donald Trump could afford to be cavalier about it.

Page 407 and 408 describing her speech to the Democratic National Convention in Philadelphia in July 2016 for Hillary Clinton

For me, Trump’s comments were another blow. I couldn’t let his message stand. Working with Sarah Hurwitz, the deft speechwriter who’d been with me since 2008, I channeled my fury into words, and then–after my mother had recovered from surgery–I delivered them one October day in Manchester, New Hampshire. Speaking to a high-energy crowd, I made my feelings clear. “This is not normal,” I said. “This is not politics as usual. This is disgraceful. It is intolerable.” I articulated my rage and my fear, along with my faith that with this election Americans understood the true nature of what they were choosing between. I put my whole heart into giving that speech.

I then flew back to Washington, praying I’d been heard.

Pages 408-409 from October 2016

In the end, Hillary Clinton won nearly three million more votes than her opponent, but Trump had captured the Electoral College thanks to fewer than eighty thousand votes spread across Pennsylvania, Wisconsin, and Michigan. I am not a political person, so I’m not going to attempt to offer an analysis of the results. I won’t try to speculate about who was responsible or what was unfair. I just wish more people had turned out to vote. And I will always wonder about what led so many women, in particular, to reject an exceptionally qualified female candidate and instead choose a misogynist as their president. But the result was now ours to live with.

Page 411

Looking around at the three hundred or so people sitting on the stage that morning, the esteemed guests of the incoming president, it felt apparent to me that in the new White House, this effort wasn’t likely to be made. Someone from Barack’s administration might have said that the optics there were bad–that what the public saw didn’t reflect the president’s reality or ideals. But in this case, maybe it did. Realizing it, I made my own optic adjustment: I stopped even trying to smile.

Page 418

Because people often ask, I’ll say it here directly: I have no intention of running for office, ever. I’ve never been a fan of politics, and my experience over the last ten years has done little to change that. I continue to be put off by the nastiness–the trial segregation of red and blue, this idea that we’re supposed to choose one side and stick to it, unable to liten and compromise, or sometimes even to be civil. I do believe that at its best, politics can be a meand for positive change, but this arena is just not for me.

That isn’t to say I don’t care deeply about the future of our country. Since Barack left office, I’ve read news stories that turn my stomach. I’ve lain awake at night, fuming over what’s come to pass. It’s been distressing to see how the behavior and the political agenda of the current president have caused many Americans to doublt themselves and to doubt and fear one another. It’s been hard to watch as carefully built, compassionate policies have been rolled back, as we’ve alienated some of our closest allies and left vulerable members of our society exposed and dehumanized. I sometimes wonder where the bottom might be.

What I won’t allow myself to do, though, is to become cynical. In my most worried moments, I take a breath and remind myself of the dignity and decency I’ve seen in people throughout my life, the many obstacles that have already been overcome. I hope others will do the same. We all play a role in this democracy. We need to remember the power of every vote. I continue, too, to keep myself connected to a force that’s larger and more potent than any one election, or leader, or news story–and that’s optimism. For me, this is a form of faith, an antidote to fear. Optimism reigned in my family’s little apartment on Euclid Avenue. I saw it in my father, in the way he moved around as if nothing were wrong with his body, as if the disease that would someday take his life just didn’t exist. I saw it in my mother’s stubborn belief in our neighborhood, her decision to stay rooted even as fear led many of her neighbors to pack up and move. It’s the thing that first drew me to Barack when he turned up in my office at Sidley, wearing a hopeful grin. Later, it helped me overcome my doubts and vulnerabilities enough to trust that if I allowed my family to live an extremely public life, we’d manage to stay safe and also happy.

Page 419 and 420

There are portraits of me and Barack now hanging in the National Portrait Gallery in Washington, a fact that humbles us both. I doubt that anyone looking at our two childhoods, our circumstances, would ever have predicted we’d land in those halls. The paintings are lovely, but what matters most is that they’re there for young people to see–that our faces help dismantle the perception that in order to be enshrined in history, you have to look a certain way. If we belong, then so, too, can many others.

I’m an ordinary person who found herself on an extraordinary journey. In sharing my story, I hope to help create space for other stories and other voices, to widen the pathway for who belongs and why. I’ve been lucky enough to get to walk into stone castles, urban classrooms, and Iowa kitchens, just trying to be myself, just trying to connect. For every door that’s been opened to me, I’ve tried to open my door to others. And here is what I have to say, finally: Let’s invite one another in. Maybe then we can begin to fear less, to make fewer wrong assumptions, to let go of the biases and stereotypes that unnecessarily divide us. Maybe we can better embrace the ways we are the same. It’s not about being perfect. It’s not about where you get yourself in the end. There’s power in allowing yourself to be known and heard, in owning your unique story, in using your authentic voice. And there’s grace in being willing to know and hear others. This, for me, is how we become.

Page 420 and 421 Epilogue–end of book